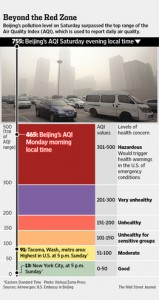

Over the past weekend, China’s air pollution reached the highest on record, reaching a level of 465 out of 500. [query: what is this scale?] As these levels generate serious health concerns, it has also become a major topic of discussion for the country’s newest leaders. As the levels rose, residents were advised to stay indoors while industrial activity was curtailed. This deterioration of China’s air quality has been a direct result of the country’s growing economy in the past thirty years. This concern has become a major obstacle for the new Communist leader, Xi Jinping, in his hopes to create a “better environment” for China. The leader was notified by the U.S. Embassy that these levels were more than 25 times the average in America.

Over the past weekend, China’s air pollution reached the highest on record, reaching a level of 465 out of 500. [query: what is this scale?] As these levels generate serious health concerns, it has also become a major topic of discussion for the country’s newest leaders. As the levels rose, residents were advised to stay indoors while industrial activity was curtailed. This deterioration of China’s air quality has been a direct result of the country’s growing economy in the past thirty years. This concern has become a major obstacle for the new Communist leader, Xi Jinping, in his hopes to create a “better environment” for China. The leader was notified by the U.S. Embassy that these levels were more than 25 times the average in America.

While officials state that they plan to address these issues, they have delayed the vote for tighter emission standards twice already. As the new leadership takes over, the hope is that regulations can be made to keep pollution down during a time of serious growth in the Chinese economy. Because Beijing has not been one of China’s 10 most polluted cities, there is fear that this [the pollution? or limiting the pollution?] will create serious harm across the country.

In the US we passed the Clean Air Act only in 1970 (though under Ronald Reagan California passed legislation in 1967). In high school I participated in the original Earth Day; a classmate collected a sample from a local river that proved to be 50% sludge, 50% water. Swimming in Lake Erie was prohibited.

So we need to be careful about pointing fingers, or rather we need to think about the politics of controlling pollution. China has lots of measures on its books. So why aren’t they enforced? Is it that they are not yet at the point the US was in when we first began to take these issues seriously? Or are there additional problems in a system where provinces have far more autonomy than do states in the US, and counties and cities are likewise highly autonomous?

Our text (Brandt & Rawski) has a nice chapter; we’ll read more elsewhere. But think about how we might count the costs of pollution, and what the costs might be of limiting pollution. Can we construct a cost/benefit analysis? Putting a monetary value on things leaves out a lot, but it at least provides a starting for talking about policy in a reasoned manner.

Constructing a cost/benefit analysis of pollution to try to provide a jumping-off point in the pollution situation certainly makes sense. However, it seems as though there are fundamental problems within the hierarchy of the powers that be in China preventing legitimate change. Professor Qu Geping, an 83-year old previously involved in policy-making in China, believes that the problem has, in the past, been that “there [is] no supervision of governments. It is because the power is still above the law”.

There is a related article on Reuters that explains how the extensive air pollution in Beijing is also beginning to affect the city’s capital. New ad-hoc rules will shut down factories, reduce activity from coal fired plants and even take certain commercial vehicles off the road. The article also mentions that with the increasing smog, lung cancer rates have gone over 60% over the last decade, and it also says that the pollution has gotten so bad that the city should be called “Greyjing”.

Clearly there is also a fundamental problem in China that involves its population. China has 3 times the population of the United States and evidently 25 times the pollution. The United States is by no means a perfect example of pollution control which only goes to show how extensive the problem is in China. It is a tough issue though because much of the world’s economic growth is controlled by the growth of China. Clearly the powers at be need to figure out a strategy to continue strong economic growth in China while also mitigating carbon emissions.

The issue of air pollution is not one that will be able to be dealt with easily. The current short-term methods of shutting down industry for a few days and suggesting that residents remain indoors is like putting too small of a Band-Aid on. Although the solutions may be costly such as filters and having to change economic structures, the change needs to happen soon. China is currently avoiding costly solutions, however by not effectively addressing the issue it is experiencing the costs in other ways. For example, lung cancer rates have shot up 60% in Beijing over the past decade despite the flattening out of smoking rates. The pollution is causing unnecessary health costs and problems that could be avoided. The global community needs to work together in order to lower the pollution rate but still attempt to maintain China’s strong economic growth.

There is little doubt that pollution is a significant problem for China moving forward. But we have to ask what is the role of government in this matter. There are three key questions to answer before the government intercedes to address this market failure: (1) How big is the externality? (2) Can victims avoid the cost? (3) What is the cost of the policy? The answers to the first two questions are obvious – air pollution is a serious problem that cannot be avoided. But what is the cost of cleaning up China’s air and water? Who will bear that burden? Does the country have the resources to accomplish its goals? Reducing pollution levels is a necessity, but it must be done in an efficient manner that minimizes costs.