While in 2014 pro-democracy demonstrations in Hong Kong made a lot of noise around the world, this current year protests against the large number of Mainland Chinese that visit Hong Kong every year have taken center stage. Although far smaller in size, the current protests are more violent and similarly fuelled by resentment of the mainland’s encroachment. At issue has been the hordes of mainland Chinese who visit Hong Kong to buy goods for black-market resale at home, a racket described locally as “parallel trading”. These new and nastier outbursts are about far more than shopping; they suggest that antagonism towards the mainland is deepening and spreading beyond the territory’s urban core. This is causing anxiety among officials on both sides of the border.

to buy goods for black-market resale at home, a racket described locally as “parallel trading”. These new and nastier outbursts are about far more than shopping; they suggest that antagonism towards the mainland is deepening and spreading beyond the territory’s urban core. This is causing anxiety among officials on both sides of the border.

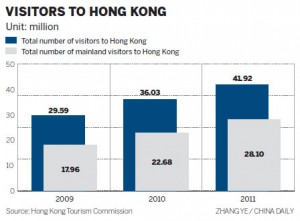

In 2002, five years after the end of British colonial rule, the Hong Kong government abolished a quota on Chinese tourists. Since 2009 residents of Shenzhen, a city adjoining Hong Kong, have been able to cross the border as often as they like. visitors have increased tenfold since 2000; last year there were 47m, an increase of 16.5% over 2013, in a city of 7m people. Some reckon there will be 100m a year by 2020. Store-owners are happy with the frenzied custom, but many locals are not. Rents have risen and many older outlets have closed. Shops catering to mainland visitors “lock out Sheung Shui culture”, says Leung Kim Shing of the North District Parallel Imports Concern Group.

Hong Kong’s government is in a bind. While it does not want to pander to anti-mainland sentiment by siding with the protesters, it also does not want to fuel the pro-democracy movement by ignoring public grievances. In my opinion, considering that these mainlanders are not actually breaking any Hong Kong laws nor doing anything ethically wrong, there is no reason to push them out. Although it makes sense for Hongkongers to oppose the mainland’s encroachment in the island this situation is different. This is not the Chinese communist government trying to tell Hong Kong’s people how to behave, but simple individuals who are trying to improve their situation. Additionally, these visitor’s are actually helping Hong Kong’s economy as they are playing the same reinvigorating role exports play in any economy.

Source: http://www.economist.com/news/china/21646794-protests-about-mainland-shoppers-reveal-graver-problems-aisles-apart

Graph:http://europe.chinadaily.com.cn/business/2012-07/02/content_15541697.htm

In the background is that the British (after ruling by decree for most of their time there) did set up Hong Kong with an elected government just before they left — so there’s the irony that as a “Special Administrative District” of the PRC there is more potential for political action than under the British. Needless to say, that can make the PRC uncomfortable. In the background: should HK be allowed to maintain its identity? If so, then conflict over the number of visitors and what they can and can’t do (buy property? set up a business?) is inevitable.

I wonder if there is any lasting sentiment from the Opium Wars in play here. I realize that it was over a century ago and has faded from the forefront, however there are some parallels. Just as the mainland Chinese are in effect using Hong Kong for their own needs with the ‘parallel trading’, so to was the case with the British when they forced their way in and continued trading opium. Both cases involve Hong Kong being used by others for their own third party economic gains. And both are also construed as instances where oppressive forces exerted unnecessary pressure on Hong Kong.

The impact of Hongkong’s rising hostile sentiment against mainlanders have already been reflected on the decreasing number of tourists in the country. Hotels were forced to cut their prices over 40% and the number of Chinese tourists decreased about 80%. The number of one day tourists who come to Hongkong for shopping daily goods is still fairly consistent but big players have already diverted their attention to Japan or South Korea.