China’s economic growth in the past few decades has been largely unmatched by developed and developing nations alike. However, until recently, China’s healthcare outreach programs have not developed at nearly as quick a rate as its economic sectors. This poses a unique problem for China, which has an aging population that is threatening to overcome China’s younger generations. Traditionally, one’s friends, family, and village provided assistance in times of medical need, as seen when Wei Jia suffers from baixuebing (白血病) in Hessler’s Country Driving. However, as larger portions of the population move from small villages to large cities, it becomes increasingly difficult for individuals to fall back on this social safety net.

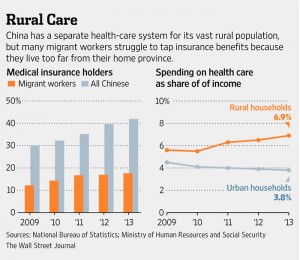

In recent years, China has begun refurbishing its healthcare system and by January 2015 it claimed that 95% of its population was covered by medical insurance. While this nominally may be true, realistically a large portion of China’s population, especially its rural populations, are unable to access this medical insurance. This arises from the fact that many individuals from rural families move to larger cities to work, however their hukou (户口), or household registration, is still located in their home province, meaning they can only access this medical insurance from the bureau of their hometown.

According to Zhang Wei, a healthcare expert at Peking University, “Coverage is fragmented and the administration of it is not desirable.” He then attributes growing individual medical costs to inherent management problems with the government, despite expansion of governmental insurance coverage initiatives.

To China’s credit, they have invested over three trillion yuan ($472.5 billion) into their healthcare system since 2009 and have increased subsidies for rural healthcare immensely. Rural health officials have recently broadened the list of illnesses that qualify for a reimbursement of 70% of personal costs, further relieving the financial burden on the individual. However, while this system is ideal for rural populations that still remain in the countryside, it still fails to provide care for 269 million migrant workers who no longer reside in the countryside. China’s healthcare system is similar to the United States in that 40% of its population gets insurance through an account funded by employers. However, an internal study done by the Chinese government found that only 18% of migrant workers have access to this employment-based system.

Wu Lailai, owner of a small restaurant in Taizou, illustrates this problem perfectly when he speaks of Zhao Guomei, a migrant worker who worked at his establishment for a few months in 2013: “I can barely remember talking to her when she was working here. How do you expect me to buy her insurance?”

Unfortunately, migrant workers work so many temporary jobs in China’s large cities that they rarely qualify for account funded medical insurance through their employers. Until this largely managerial problem is solved, China’s younger working populations face the prospect of not being eligible for medical assistance in the large cities they work in should they contract some type of illness. China therefore must work to not only care for its rapidly growing geriatric population but also its woefully under-covered working population—an initiative the will require large scale reform and significant financial investment.

http://www.wsj.com/articles/falling-through-the-cracks-of-chinas-health-care-system-1420420231

Hessler, Peter. Country Driving. New York: HarperCollins, 2010.

– If 70% of costs are covered, what of the other 30%? Can an older peasant woman afford this?

– And is this coverage at official medical prices, or at the price that doctors charge?

– How many clinics and where? In much of China, getting to and from the nearest large town is not easy if you are a poor peasant.

– Is pay such that a clinic will actually have a doctor?

– Who actually funds?

See China 2030 (link on course web site) for a chapter with more details. Not all of the questions I pose have clear answers.

What is the quality of healthcare (those that receive it) throughout China? Do individuals that have access to doctors receive adequate treatment, or does that require additional, bribe-like funds to receive the treatment one needs?

Is there a process in which migrant workers can switch their location in order to receive healthcare benefits where they currently work?

Look for that in the Miller book and subsequent readings this term.