In terms of innovation, the Chinese model is led by the state, which selects several areas of importance and gives them copious funding in order to lead innovation and produce more research in that specific sector. While this has been successful in targeting and improving many sub-fields, many economists do not feel that this approach will work in the long term.

The pressure is on for China to keep up the record levels of economic expansion it has seen in the past few decades, however; with the rate of economic growth decreasing from 10.4% to 7.5% in the past 2 years, many people worry that further decreases are eminent if China’s growth model stays the same. Those who are worrying have doubts about a successful future with China’s reliance on imitating western goods instead of innovating.

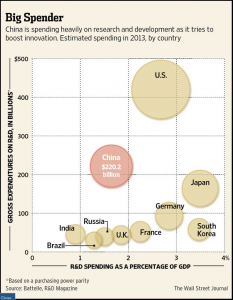

Source: Wall Street Journal

Economists are at odds with each other about what China’s growth model should look like. Some feel that China still has the ability to succeed by imitating western technologies as long as they can produce them more cheaply. Other economists believe that innovation and inventions are at the root of market growth, without unique innovations, an economy cannot sustain long-term economic growth.

China faces many struggles with innovation because the government doesn’t do very much to protect intellectual property. Another obstacle is the importance placed upon headline-grabbing technological innovations instead of more practical but less publicized innovations, which could create new industries.

Source: http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304795804579099640843773148

Innovation, stemming from overall human capital appreciation, is an important input for economic success. China’s, relatively speaking, lack of expenditures on R&D due to its current economic model will eventually negatively impact the Chinese growth rate. Unless there are fundamental structural changes to the economy, which are increasingly occurring, the growth of the labor force and governmentally targeted investment can only go so far. This ties into the Nam article regarding joint ventures. In many cases, IJVs do provide mutually beneficial partnerships between a foreign and a domestic firm, yet the two companies do not bring the same type of inputs to the table. Regarding China, the domestic firm provides access to the target market, labor force, governmental access, etc., while the foreign firm provides the technological and productive “know-how,” and, more importantly, the innovative human capital. The Chinese workforce quickly adapts to improve their productivity; however, because their skillsets increasingly become dependent on western blueprints and directions, they do not garner the innovative skillset to operate autonomously on a long-term basis.

Income per capita is partially derived from the marginal product of labor, which can be improved through developing technology, physical capital, and human capital inputs. The country has clearly been improving the first two, but the later input requires intellectual property rights, for example, to be enforced (as Marybeth highlights). By fostering an economy where innovation can develop in any sector, rather than only government targeted sectors, entrepreneurs can better flourish and the average prosperity of the country will rise. Education, albeit still very expensive, has been increasingly permeating the Chinese society, a promising first step. As the overall education level rises and financial markets continue to liberalize, I believe that the issue highlighted by this article will resolve itself. Research and development will increasingly become a larger percentage of China’s economy, further signaling its development, while benefiting average income per capita.